A Brief History

On May 10, 1849, Astor Opera House in Manhattan was the unlikely scene of another of those goofy named riots we keep telling you about. Though the Astor Opera House is no more (nor are the 22 to 31 people killed during the riot!), the Astor Place Riot lives on in the Pantheon of Stupid Riots. (Type in “Riot” in the question box of our website to get our many articles about the seemingly endless supply of riots.) Along with the many people killed, another 260 (including militiamen) were seriously injured, making the Astor Place Riot one of the most deadly in the history of Manhattan Island, and even the deadliest military related incident for civilians since the American Revolution as the State Militia was called to assist the police in putting down the riot. Incredibly, the riot began as an outgrowth of a feud between 2 of the leading actors of the day.

Digging Deeper

Those actors at the center of the rivalry were British actor William Charles Macready and his American counterpart, Edwin Forrest. Both men were renowned Shakespearian actors and had developed a rivalry after initially being on a friendly basis. Macready was the established star, as British actors and production specialists had dominated the theater scene even in America. Forrest was the up and coming American star, and both men had quite the following, being equivalent to mega-movie stars today. The subject of Shakespeare in the theater also dominated the stage in those days, even prompting poet and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson to quip, “beings on other planets probably called the Earth ‘Shakespeare.’” All classes of American theater goers seemed to favor Shakespeare productions, even on the frontier.

Another factor in the inflamed passions that led to the rioting was the Nationalism felt by Americans that manifested itself in a somewhat anti-British and anti-immigrant sentiment. Oddly enough, although Americans born in the US generally dislike the recent crush of immigrants from Ireland, even those Irish immigrants were inclined toward an anti-British outlook. Way back in 1765, when the Stamp Act enraged Americans, a theater with a British production was torn apart, and the anti-British sentiment had continued to fester in the United States.

Still another factor that fed the flames of riotous fomenting was the cultural/class gap between the rich and privileged people that generally tended toward the British elite theater productions and the lower/working classes of Americans that preferred the home grown productions and stars. Class and economic inequality became class and economic envy and resentment, just waiting for a match to light the bonfire.

Both of the actors at the center of the controversy had toured both England and the US, and Forrest had taken the irritating habit of following around Macready as the British actor toured, engaging in performances of the same plays that Macready was performing in an effort to prove through the rival productions that Forrest was the superior actor. Forrest had also hissed at a performance by Macready, a display of poor sportsmanship that Macready decried as lacking in proper taste. Forrest also sued his wife for divorce, the English woman actually winning the case on the same day Macready arrived in New York to begin what was supposed to be his final tour, souring Forrest’s already foul mood.

The Astor Place Opera House had run into hard times trying to fill all its seats for operatic productions, and was relegated to also showing various plays, calling itself the “Astor Place Theatre.” As Macready prepared to perform in Macbeth, so Forrest was performing in a production of Macbeth not far away at the larger Broadway Theater. Forrest’s supporters bought out many of the tickets to the Macready 3 scheduled performances starting May 7th and came loaded with ammunition to throw at Macready and the other actors, including fruits, vegetables, rotten eggs, shoes and other garbage! Angry Americans ripped up their seats and booed and hissed at the actors who could not even be heard above the din. Though the British troupe tried to carry on, though without speaking their lines while the Americans yelled colorful phrases such as, “Shame, shame!” and “Down with the codfish aristocracy!” Meanwhile, American audiences were cheering for Forrest at the other venue.

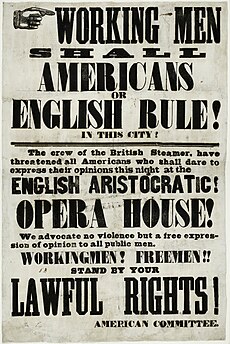

Macready was not surprisingly disgusted with performing in New York and stated his intention to leave the US without performing any more plays. He was persuaded to act once again in another performance of Macbeth on May 10, 1849, and the poor man let himself go down that dangerous path! The police and politicians were not unaware of the dangerous mood of the people, and the State Militia was summoned in advance of any problems to be at the ready. Along with the 100 policemen assigned to the theater, another 350 troops were also designated for possible riot duty. Meanwhile, the rabble rousers among the population had been circulating posters and bills around town, inviting Americans to come and show the British up at the Astor Place, and about 10,000 supporters of Forrest and the American Way showed up to school the British about who was and was not welcome in New York. Even some local politicians had taken part in fomenting the violence that followed. Among the angry mob was famous pulp fiction novelist Ned Buntline (real name Edward Zane Carroll Judson Sr.), a fervent supporter and fan of Edwin Forrest.

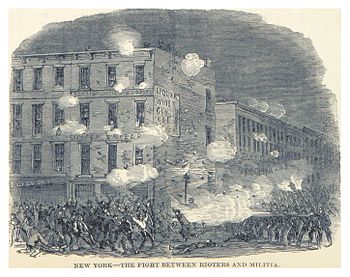

When the 7:30 pm show started, so did the riot. Rioters bombed the theater with bricks, rocks and various projectiles, while police chased rioters around, hopelessly outnumbered by the mob. Theater goers had been screened for carrying “ammunition” and other contraband, but enough Forrest supporters got in to somewhat disrupt the show while the theater was under attack from the outside. Macready and the cast once again had to act without speaking, as they could not be heard above the clamor. The bewildered police called for the militia and the riot was stepped up a notch.

Responding Militiamen fired into the air to disperse the crowd, and failing to have noticeable effect, began shooting rioters. Of course, rioters had been pelting the police and militiamen with rocks and such, a questionable idea when dealing with armed men. Local buildings suffered damage from thrown rocks and fired bullets, and many of the dead and injured were mere bystanders. Virtually all of the dead were of the lower/working classes. The fusillade of gunfire finally dispersed the rioters, leaving the dead and injured in the streets. Although no policemen or militiamen were killed, about 50 to 70 of the police were injured and another 141 militiamen were also injured.

On May 11, 1849, a city meeting was held, and enraged citizens expressed their extreme displeasure at the authorities that had allowed a bloodbath to develop. Another riot began, and a boy was killed. This new riot was put down decisively and without delay. Public impressions about the incident were polarized on class lines, with the upper class people praising the authorities and the militia while the working class and poor people were outraged by the use of government force against the public. Class struggle had found its way into the theater, and productions of Shakespeare’s plays became something only for the well to do.

As for the Astor Place, disparagingly referred to as the “DisAstor Place,” the venue could not survive as a theater and the building was sold to the New York Mercantile Library. A new theater that catered to the wealthier classes, Academy of Music, was opened in a wealthier neighborhood not frequented by the lower classes.

Once again, people had proven their willingness to riot over idiotic things, this time over which actor was the better portrayer of Shakespearian characters. Can you imagine a riot today over whether or not Sean Connery or Daniel Craig was the better James Bond? A riot that cost a couple dozen lives? To quote from the hilarious Michael Nesmith video production, Elephant Parts, “People are just no damn good!”

Question for students (and subscribers): What is the most idiotic reason you have heard of for a riot? Have you ever been “fighting mad” about a disagreement about a singer or actor? Please let us know in the comments section below this article.

If you liked this article and would like to receive notification of new articles, please feel welcome to subscribe to History and Headlines by liking us on Facebook and becoming one of our patrons!

Your readership is much appreciated!

Historical Evidence

For more information, please see…

Moody, Richard. The Astor Place Riot. Indiana University Press, 1958.

Ranney, HM. Account of the Terrific and Fatal Riot at the New-York Astor Place Opera House, On the Night of May 10Th, 1849: With the Quarrels of Forrest and … Wherein an Infuriated Mob Was Quelled by T. Ulan Press, 2012.

Toppin, John. The Night Shakespeare Literally Killed The Audience: The Story of The Astor Place Riot of May 10, 1849. Independently published, 2019.

The featured image in this article, Astor Place Opera-House riots cropped by Beyond My Ken (talk) 11:03, 23 October 2010 (UTC), is in the public domain in the United States. This applies to U.S. works where the copyright has expired, often because its first publication occurred prior to January 1, 1924. See this page for further explanation.