A Brief History

On June 2, 1692, the trial of Bridget Bishop began, starting a reign of terror in Salem, Massachusetts known as The Salem Witch Trials. The hysterical idiots responsible (unless you believe in witches) executed (by hanging) 20 people from 1692 to 1693 before the madness ended. Scores of others had been accused, many of whom confessed to avoid execution, and scores were imprisoned. At least five of those imprisoned died while in jail. Cracked fact: No “witch” was burned at the stake in these trials. Execution was by hanging.

Digging Deeper

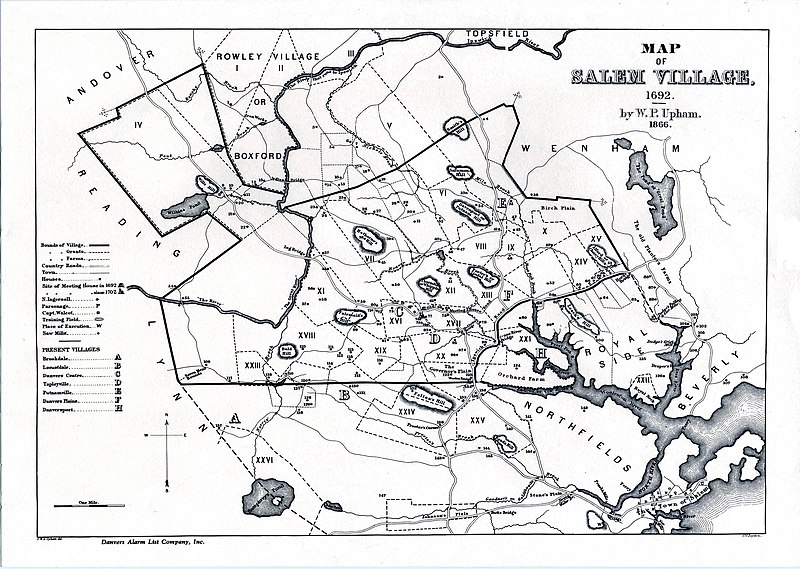

Despite the common name of this mass hysteria, the trials and executions took place in several nearby settlements as well as Salem. Also, this incident was not the first case of people being accused of witchcraft in Massachusetts, as prior to 1692 at least 12 executions for witchcraft in New England had taken place, the majority in Massachusetts.

The backdrop of these trials was a colony where people just did not get along well. Disputes over property lines, debts, and religion were rampant, and tolerance was a virtue seemingly absent from the settlements. In addition to the tensions already present, rabble rousers like the preacher Cotton Mather stirred the pot by going on at length about “stupendous witchcraft,” writing pamphlets and a book about the subject. The already superstitious colonists were made paranoid by such warnings.

The dynamite was set and fused, and some young girls provided the match. Acting strange, throwing fits and convulsions, obviously (to the primitive minds of the colonists) the girls were victims of witchcraft. Suspects were rounded up, starting with women seen to be odd: the homeless or eccentric, and generally disliked, including a slave woman (Tituba, probably a Native American).

The floodgates were now open, and rival families began to accuse women of each other’s family of witchcraft, resulting in 72 people (mostly women) being arrested, interrogated, and held for trial. Other suspects, rightfully fearful of being falsely convicted, went into hiding or fled. Of course, fleeing then like now was seen as the action of a guilty person and warrants were issued for the arrest of fugitives.

The trials started with Bridget Bishop, tried and convicted on the same day, and executed by hanging a week later. Meanwhile, Cotton Mather continued to stir the pot with his anti-witch pronouncements and condemnation of those that would cavort with the devil. Witnesses testified that they had personally seen the accused engaged in a variety of satanic activities, and some of those accused gave colorful confessions of such activities themselves in an effort to avoid execution.

One of the key tests to prove witchcraft was to have the accused touch a victim while the victim was in the throes of a fit, and if the victim immediately recovered, the accused was obviously the person that had bewitched the victim. (Obviously. Could not possibly be framing the accused.)

When the trials finally ended, so did the madness, with many voices speaking out against the unjust trials and executions. Within just a few years the trials had gained notoriety as what we today would call a “witch hunt.” People today are not immune to hysteria over witches, and even a pastor of ex-Alaska governor Sarah Palin has engaged in persecution of witches in these supposedly modern times!

Question for students (and subscribers): Why have witches (or suspected witches) been persecuted in history? Please let us know in the comments section below this article.

If you liked this article and would like to receive notification of new articles, please feel welcome to subscribe to History and Headlines by liking us on Facebook and becoming one of our patrons!

Your readership is much appreciated!

Historical Evidence

For more information, please see…

Roach, Marilynne K. The Salem Witch Trials: A Day-by-Day Chronicle of a Community Under Siege. Taylor Trade Publishing, 2004.

The featured image in this article, Bishop, as depicted in a lithograph, is in the public domain in the United States because it was published (or registered with the U.S. Copyright Office) before January 1, 1926.