A Brief History

On August 2, 1916, Austrian saboteurs managed to sink the Italian battleship, Leonardo da Vinci as the great ship lay in Taranto harbor. Was the magazine explosion an accident, or did the Austrians use some sort of novel booby trap to sink the mighty vessel? Either way, World War I, like other wars, saw the imagination of arms designers and military engineers run wild. Previously we have discussed 10 Weird Weapons of World War I, and today we expand our list by another 5 goofy gadgets both sides came up with to pursue victory in this terrible war. (Note: Not every item is necessarily a “weapon,” but is an implement of war.)

Digging Deeper

1. Aerial Darts and Lazy Dog Bombs.

Remember “Jarts?” Also known as “Lawn Darts?” These deadly toys were banned when happy families playing in the back yard found out that the pointy end could be dangerous to people if the lawn dart landed on the person. During World War I, when aerial warfare was still in its experimental stage, the idea that dropping things from the sky onto the noggins of the enemy soldiers could cause casualties and perhaps even demoralize the enemy troops. Dart type objects with pointy steel ends and a trailing body of feathers (similar to a small version of an arrow) were dropped on troops on the ground. The widespread use of steel helmets quickly diminished the effectiveness of these so called “flechettes.” Another take on the same idea was the “Lazy Dog Bomb,” alternatively known as the “Red Dot Bomb” or “Yellow Dog Bomb.” Unlike the exploding bomb that comes to mind when the words “aerial bomb” are used together, these bombs contained no explosive charge at all. They were just aerodynamically shaped steel bombs with metal fins on one end and a pointy ogive on the other end. Like the flechettes, these hunks of metal were designed to kill and injure through kinetic energy alone. By 1916 the geniuses in charge finally scrapped these non-exploding devices for proper exploding bombs.

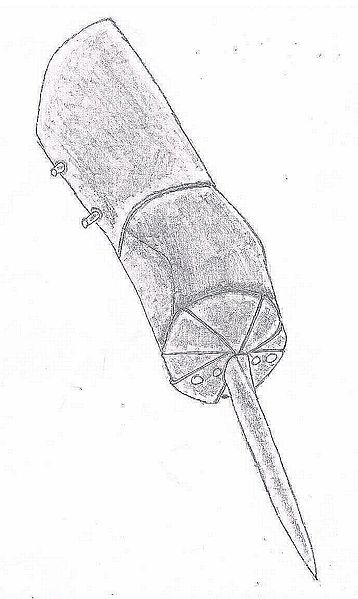

2. Gauntlet Dagger.

When a plain old bayonet or trench knife was not good enough, the English and French gave their men in the trenches a weird weapon better suited for medieval times, a so called “gauntlet dagger.” This old time device consisted of a push dagger blade extending from a rigid sleeve made of leather or metal that went over the hand and wrist of the soldier using it. The soldier would then use it to punch holes in his close combat foe. You may have seen this weapon depicted in video games such as Assassin’s Creed. To us at History and Headlines, it seems as if storing this device on one’s belt or other gear must have been awkward! The horrible hand to hand fighting in the trenches spawned such barbaric devices as revolvers equipped with bayonets and trench knives equipped with studded brass knuckles to go along with the Gauntlet Dagger and Trench Clubs.

3. Standschütze Hellriegel M1915.

The idea of a light machine gun, such as an automatic rifle or submachine gun had occurred to many firearms designers during World War I and a variety of such weapons were made. The fine American Browning Automatic Rifle and Thompson Submachine Gun did not make it to the war in time to leave a mark. One of the weirder efforts to capture the benefits of automatic fire in a weapon carried by a single soldier was the Austro-Hungarian Standschütze Hellriegel M1915, a shoulder arm of 9 x 23mm Steyr caliber (similar to the more familiar 9mm Luger or 9mm Parabellum cartridge). This large sized submachine gun (an automatic hand held weapon that fires a pistol caliber cartridge) was fed by a large drum magazine containing perhaps 120 rounds or a box style magazine containing 20 or 30 rounds. Its exact weight and length is unknown, though the beastly weapon looks awful heavy for one soldier to carry around. This weapon may not have ever been used in combat and details are sketchy. Why can we say this gun was heavy if we do not know the actual weight? Because it was water cooled! The water and water jacket would certainly add considerable heft to the weapon and increase its bulk. What were they thinking? Of course, such a nifty looking weapon appears in a video game, in this case Battlefield 1.

4. Huot-Ross Automatic Rifle.

Joseph Huot was a Canadian weapons designer that was pondering the answer to the question of how to effectively equip Canadian troops with a light machine gun or automatic rifle quickly and economically in time to be of use during World War I. He came up with the novel idea of using the thousands of Ross bolt action rifles that had been taken out of service in 1916 and converted them into automatic rifles fed by a 25 round drum magazine. Firing the British .303 cartridge, the Huot could spit lead at a rate of 475 rounds per minute, quickly emptying its magazine which was awkward to carry though easy to change a full magazine for an empty one, taking 4 seconds to change magazines. The weapon weighed 19 pounds when loaded, which was par for the course at the time, but never made it to mass production although the prototype guns were actually used in France for combat testing. The American designed Lewis Gun was used instead, although the Lewis was much heavier at about 28 pounds. The Huot would probably have been a better weapon than the much maligned French Chauchat automatic rifle that saw widespread use by the Allies during World War I. Not to be outdone, the United States developed the Pederson Device for their M1903 Springfield rifles. This contraption was a drop in unit that allowed the use of a 40 round box magazine containing .30 caliber (7.62mm) pistol cartridges that could be fired in a semi-automatic mode for close combat in trenches where long range and extra penetration was not needed. Although accepted in 1918 and 65,000 of the devices, along with a staggering 65 million cartridges to fill the 1.6 million magazines manufactured and over 100,000 Springfield rifles modified, the device never made it to Europe in time to become involved in combat. Sadly, nearly all the devices were eventually scrapped by the US Government, and there are probably less than 10 original devices in existence today.

5. Artillery Luger Submachine Gun.

As the military forces of each of the combatants in World War I realized the need for a handy submachine gun the Central Powers forces came up with a “solution” by adapting the Artillery variant of the Luger P08 pistol into a fully automatic machine pistol. The result was a bizarre looking long barreled (7.9 inch) Luger P-08 with a wooden shoulder stock and an ungainly looking 32 round capacity snail drum type of magazine. In keeping with the idea of merely converting an extant pistol to fire full automatic with an enhanced magazine, the Germans also adapted the C 96 Mauser pistol in this manner, but the Luger submachine gun wins the prize for the oddest looking. While the Luger submachine gun ended production with the end of World War I, the C 96 Mauser conversion submachine gun was revived in Spain during the 1920. Another Central Powers weapon, the Repetierpistole M1912/P16, was the first practical machine pistol and looked pretty conventional except for the extralong (16 round) magazine that stuck out from the bottom of the magazine well. The concept of an automatic pistol (as in “full” automatic as a machine gun) is still in favor today, and Beretta makes such a version of their famous Model 92 pistol (called the Model 93R) with a small fold down front handle for use in full automatic fire (3 round bursts)

Question for students (and subscribers): As always, feel free to nominate whatever other odd or innovative weapons or systems you believe belong on this list in the comments section below this article.

If you liked this article and would like to receive notification of new articles, please feel welcome to subscribe to History and Headlines by liking us on Facebook and becoming one of our patrons!

Your readership is much appreciated!

Historical Evidence

For more information, please see…

Bishop, Chris. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War I. Amber Books, 2014.

Webster, Wayne. Weird and Unusual Weapons: Firearms and their Development. BookRix, 2016.

The featured image in this article, a postcard of Leonardo da Vinci in Taranto, is in the public domain in the United States because it was published (or registered with the U.S. Copyright Office) before January 1, 1924. The country of origin of this photograph is Italy. It is in the public domain there because its copyright term has expired. According to Law for the Protection of Copyright and Neighbouring Rights n.633, 22 April 1941 and later revisions, images of people or of aspects, elements and facts of natural or social life, obtained with photographic process or with an analogue one, including reproductions of figurative art and film frames of film stocks (Art. 87) are protected for a period of 20 years from creation (Art. 92). This provision shall not apply to photographs of writings, documents, business papers, material objects, technical drawings and similar products (Art. 87). Italian law makes an important distinction between “works of photographic art” and “simple photographs” (Art. 2, § 7). Photographs that are “intellectual work with creative characteristics” are protected for 70 years after the author’s death (Art. 32 bis), whereas simple photographs are protected for a period of 20 years from creation.