A Brief History

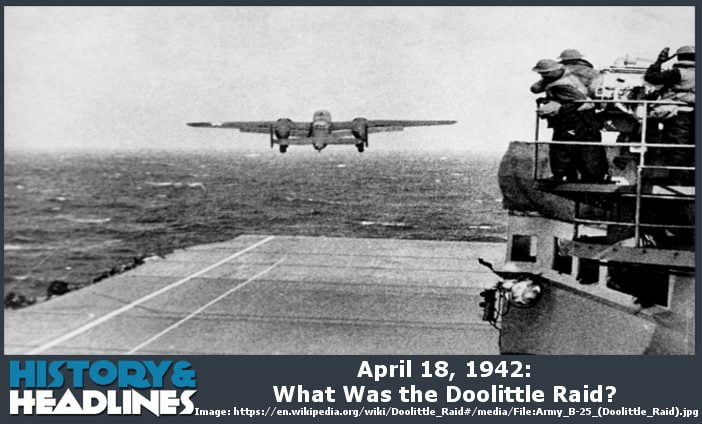

On April 18, 1942, Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle led one of the most famous bombing raids in aviation history when he led 16 B-25 medium bombers over Tokyo, Kobe, Nagoya, and Yokohama, Japan. After the devastating sneak attack against Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the US military in the Pacific was reeling, as was the shocked and furious American public. With one Japanese success after another, the US finally mounted an offensive action by flying 16 stripped down B-25B Mitchell twin engine medium bombers off the deck of the USS Hornet, something that had never been done at that time.

NOTE: On April 9, 2018, the last surviving Doolittle Raider, Lt. Colonel Dick Cole, age 103, died in Texas. He had been hospitalized at the Brooke Army Medical Center and had been visited by numerous dignitaries, including the Secretary of the Air Force.

Digging Deeper

The bombers, led by the famous military and civilian pilot Jimmy Doolittle, bombed Tokyo and other Japanese cities causing light damage, but giving America a tremendous boost in morale. At the same time, the Japanese public and military were dealt a crushing blow in morale, and for the rest of the war numerous Japanese fighter planes were diverted from front line theaters to defend the homeland against potential future raids. The dangerous nature of the raid, accepted as a possible suicide venture, is demonstrated by the loss of 15 of the 16 bombers, and the deaths of 7 of the 80 airmen involved. (3 died in action, 4 died in captivity, 3 of which were executed). Another 4 crewmen lived out the war as POW’s. Doolittle received the Medal of Honor and a promotion to Brigadier General and went on to command other bomber units.

The bomber chosen for the sorely needed answer to Pearl Harbor was the North American B-25B Mitchell twin engine medium bomber, the only American bomber with the range and ability to take off from an aircraft carrier deck that could also deliver a reasonable payload. For the Doolittle Raid, the planes were stripped of excess guns and weight and equipped with extra gas tanks, doubling the fuel load. The bomb load selected for each bomber was 3 X 500 pound normal aerial blast bombs and a 4th 500 pound bomb constructed with explosives and incendiary devices. Select crews of 5 men per bomber practiced short takeoffs on land until they could consistently take off in the few hundred feet allowed by a carrier deck. (The only US warplane named after an actual person, the B-25 was the premier medium bomber of World War II and served until 1979 with the Indonesian Air Force! Carrying as many machine guns as the larger B-17 and B-24, no other light bomber could defend itself like the Mitchell. Superb in the low altitude ground attack role, some B-25’s were equipped with the ability to fire 16 .50 caliber machine guns forward for strafing! In addition, some models were equipped with a forward firing 75 mm howitzer, the heaviest forward firing armament on any plane ever! The almost 10,000 B-25’s saw service with all branches of the armed forces and was famous as the bomber used in the “Doolittle” raid on Japan. The B-25 was one of the most versatile American aircraft of World War II.)

Unfortunately for the raiders, the USS Hornet and its accompanying fleet was spotted by a Japanese fishing/patrol boat prior to reaching the planned takeoff point, still 650 nautical miles from Japan, instead of the planned 480 nautical mile distance. The Japanese boat was quickly sunk, but in the event it had gotten off a radio warning (it did) a choice had to be made: scrap the mission or send the bombers right now, with the strong possibility the planes could not make safe landfall in China due to the extra 170 nautical miles from the planned launch point. The decision to send the bombers was a foregone conclusion, and all 16 of the heavily laden aircraft took off successfully and delivered their bomb loads as planned. No bombers were shot down despite light anti-aircraft gunfire and minor fighter interception, and one of the bombers actually shot down a Japanese fighter plane. Damage to Japan was slight, but the raid rocked Japanese confidence and security, while news of the raid caused jubilation in the United States.

The extra distance to the proposed Chinese landing sites coupled by a headwind meant the planes would not make their scheduled landings. One bomber landed in the Soviet Union and was impounded by the Soviets, the crew interned until 1943 since the USSR was not at war with Japan. The other 15 bombers flew to China, all either crash landing or crashing after the crew bailed out. The planned for homing beacons to be sent from Chinese landing fields were never transmitted, because Admiral Halsey, the task force commander, never sent the radio message to do so, probably to avoid his ships being found by Japanese radio direction finding analysts. Of the 75 crewmen that landed in China, 3 were killed in action, 3 were executed by Japanese soldiers, 4 spent the war in POW camps, and the remainder were eventually repatriated to American forces.

The Doolittle Raid had little impact on Japan’s war industry, but nervous Japanese planners kept considerable anti-aircraft artillery and interception aircraft in Japan that could have been put to good use elsewhere, giving the Raid a disproportionate impact on the War. Japanese military and civilians were taken aback by the realization their country could be bombed, a severe blow to their confidence. Americans smugly rejoiced in the retribution for the Pearl Harbor attack and the fact that the US Army and US Navy proved that land-based bombers could be flown from aircraft carriers impressed the world.

Doolittle himself, a record breaking pilot before the War, landed in his parachute in a large dung pile in China, a soft landing, but a messy one! He had also thought he landed in a dung pile figuratively as well, thinking the loss of the aircraft would result in a court martial for himself. He was wrong and was awarded the Medal of Honor and given a promotion. The other crewmembers were decorated and began a tradition of meeting annually on April 18th to toast their lost comrades. Only one crewman from the famous Doolittle Raid survives today (as of when this article was written, see note above about his death), Col. Richard Cole, age 102, the co-pilot for Doolittle himself. Doolittle died at the age of 96 in 1993.

The Doolittle Raid ranks among the most famous bombing raids in aviation history, and Jimmy Doolittle ranks among the most famous bomber pilots/tacticians in military history. The B-25 bomber was one of the most versatile and useful medium bombers of World War II, and a whopping 9800+ were built, the most of any US medium bomber.

Question for students (and subscribers): Can you think of a more famous bombing raid of World War II? Please let us know in the comments section below this article and see our articles for more about bomber people and bomber aircraft: “10 Greatest Bombers,” “10 Famous Bombers,” “10 Great Military Feats,” “6 Versatile Aircraft.”

If you liked this article and would like to receive notification of new articles, please feel welcome to subscribe to History and Headlines by liking us on Facebook and becoming one of our patrons!

Your readership is much appreciated!

Historical Evidence

For more information, please see…

Doolittle, James. I Could Never Be So Lucky Again. Bantam, 1991.

Glines, Carrol. The Doolittle Raid: America’s Daring First Strike Against Japan. Schiffer Publishing, 2000.

Lawson, Ted. 30 Seconds Over Tokyo. Pocket Star, 2004.

The featured image in this article, a U.S. Navy photograph of a B-25 taking off from USS Hornet for the raid, is a work of a sailor or employee of the U.S. Navy, taken or made as part of that person’s official duties. As a work of the U.S. federal government, it is in the public domain in the United States. This media is available in the holdings of the National Archives and Records Administration, cataloged under the National Archives Identifier (NAID) 520603.