A Brief History

On October 14, 1943, the United States Army Air Force conducted one of the most catastrophic bombing raids in history, catastrophic for the bombers, that is! In 1943, World War II was still in serious doubt as to the outcome, and the United States and its key ally, Great Britain, were wracking their brains for the most efficient way to diminish German war making potential. Under enormous pressure from the Soviet Union to open a second front in Northern Europe, the US and UK elected instead to bring the land war to the Mediterranean Theater of Operations and to attack Germany through concentrated aerial bombardment, the first attempt at strategic bombing of an enemy to destroy that enemy’s war making ability. At this point in the war, the rewards for the Allies’ efforts were minimal, though at great cost.

Digging Deeper

The RAF had learned already that their heavy bombers did not have the defensive firepower necessary to defend against enemy fighters and interceptors, and that their service ceiling was well within the range of ground based anti-aircraft artillery, also known as “flak.” British fighters had nowhere near the range needed to defend bombers over Germany, and thus the RAF planners realized night bombing of area targets was the only realistic strategic bombing goal. Although the British aerial brass tried to explain this reality to American airmen, the Americans insisted on performing daylight “precision” bombing of specific targets, believing their heavily armed B-17 and B-24 bombers, each with 10 or 12 defensive heavy machine guns could fight their way to and from the target. The reality was that American fighters, though possessed of longer range abilities than their British counterparts, also did not have the range needed to effectively protect the bombers over Germany. Even though the American bombers had a higher service ceiling, they were still well within range of German flak. The American sophisticated Norden bombsight was believed to provide pinpoint accuracy, but the reality of war, often different than on the papers of those planning the war, was that American bombing accuracy was not much better than the British effort. Still, the Americans insisted on planning and carrying out daylight attacks. So much effort went into the development of the technology of heavy American bombers and their related equipment, and the massive production of mass quantities of those aircraft, the temptation to use the planes as designed was overwhelming.

Another major factor in planning strategic bombing campaigns is target selection. Instead of trying to bomb every single worthwhile target and thus watering down the effect of the bombing, by concentrating on a few vital resources it is possible for the bombing force to negate the effects of other aspects of enemy war fighting ability. An example would be to shut down enemy oil and fuel production, which would ground their air force and bring their ground vehicles to a halt. If you could totally shut down fuel and lubrication, you would not have to target plane and vehicle factories. Likewise, the production of ball bearings was deemed a strategically vital target, as virtually all vehicles, aircraft, engines of all types, and many weapons need ball bearings to operate properly if at all. The center of ball bearing production in Germany happened to be at Schweinfurt, where nearly half of German ball bearing production took place. While American planners eagerly and optimistically predicted American bombing of ball bearing factories would cripple the German war effort, British planners counseled that such optimism was a pipe dream. American aerial assault on Schweinfurt began in August of 1943, with a massive and costly raid that target analysis claimed decreased ball bearing production by a third. On that first Schweinfurt raid, 376 bombers were sent, with the massive loss of 60 bombers and their crews. Compounding the miscalculation, American strategists had not reckoned on the fact that the Germans had amassed a considerable stockpile of spare ball bearings and an interruption in production was in fact not a major set back to the German war effort. Nonetheless, buoyed by the “success” of the first raid, another massive raid was planned for October of 1943, one in which 351 heavy bombers were scheduled to take part. Although P-47 fighters were assigned as escorts, those fighters did not have auxiliary fuel tanks (drop tanks) installed and could only fly part of the mission, leaving the bombers on their own for the most dangerous parts of the mission.

The second Schweinfurt mission went ahead with 291 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers assigned to Schweinfurt and an additional 60 Consolidated B-24 Liberators diverted to another target. The many P-47’s assigned escort duties had to turn back after only the first leg of the mission, as did British Spitfire fighters also assigned as escort. The squadrons of Spitfires reappeared for the final leg of the journey home of the bombing force, but by then it was too late as the bombers had been devastated. A total of 229 of the B-17’s hit the city of Schweinfurt, including the intended ball bearing plants, causing considerable damage, enough so that ball bearing production was greatly diminished for the next 6 weeks. Unfortunately, that period of diminished production had almost no effect on the German war effort. The bombers, left unescorted over the target area, were ravaged by flak and German fighters, about 7 squadrons of Me-109 (or Bf-109, if you will) and FW-190’s. Allied claims of 186 German fighters shot down were highly exaggerated, with a real count of about 3 dozen German fighters downed and another 20 damaged. American losses were horrific, with 77 B-17’s shot down or junked upon landing and another 121 seriously damaged. The American bombing campaign was temporarily crippled by the enormous losses, which included nearly 600 American aviators killed, another 43 wounded, and 65 taken prisoner. The US also lost 4 P-47 fighters. Schweinfurt would not be attacked again for over 4 months, and by then the Germans had taken measures to disperse ball bearing production. Deep penetration bombing raids into Germany were halted by the USAAF until P-51 Mustang fighters could be fielded in sufficient numbers to provide escort for the bombers. During 1944 and 1945, the combined American/British bombing offensive reached new levels of destructive airpower and finally had a major impact on Germany’s war making ability.

The strategic bombing campaigns against German and Japanese targets, including area targets such as cities, remains controversial among historians both for the debate about its effectiveness and for the ethical and legal considerations involving such attacks in which large numbers of civilians are killed and displaced. Certainly, retaliation for Axis bombing of civilians was part of the equation as Allied planners decided on a bombing strategy. United States bombers dropped over 1.4 million tons of bombs on Germany and German held territory, while the RAF added another 1.3 million tons, the combined weight of which killed over a half million Germans. Both the US and UK lost over 79,000 aviators apiece in the massive strategic bombing effort. The Western Allies suffered the loss of over 33,000 aircraft from all causes over Europe! (See our many other articles about bombs, bombing and bombers.)

Question for students (and subscribers): Is the bombing of civilians legal if military targets are destroyed at the same time? Please let us know in the comments section below this article.

If you liked this article and would like to receive notification of new articles, please feel welcome to subscribe to History and Headlines by liking us on Facebook and becoming one of our patrons!

Your readership is much appreciated!

Historical Evidence

For more information, please see…

Caidin, Martin. Black Thursday: The Story of the Schweinfurt Raid. Independently published, 2019.

Vlaun, Brian. Selling Schweinfurt: Targeting, Assessment, and Marketing in the Air Campaign Against German Industry. Naval Institute Press, 2020.

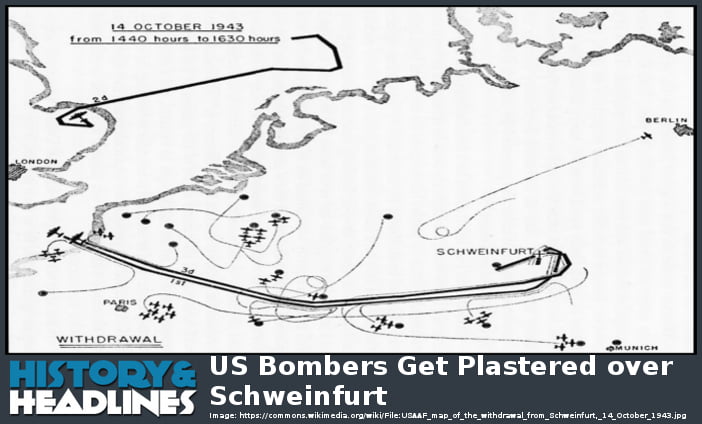

The featured image in this article, a USAAF map of the withdrawal from Schweinfurt, 14 October 1943, is a work of a U.S. Army soldier or employee, taken or made as part of that person’s official duties. As a work of the U.S. federal government, it is in the public domain in the United States.