A Brief History

On September 12, 490 BC, an epic battle was fought between the Greeks (primarily Athenians) and the Persian Empire at the plains of Marathon, Greece, about 26 miles from Athens, with the result being a great victory for the outnumbered Greeks and giving rise to the legend of Pheidippides running the long distance to bring news of the victory to Athens, giving the happy word with his dying breaths. The battle marked a turning point in the power struggle between the Greeks and Persians and resulted in a period of Greek sovereignty over their own land.

Digging Deeper

The Battle of Marathon came about as a Persian invasion of Greece was mounted in order to punish and subjugate Athens for that city-state having the gall to incite revolution in Ionia against Persian rule. Persian King Darius I sent an invasion force of 600 triremes carrying 100,000 sailors (which would serve as a reserve land force) along with a main force of 25,000 infantry troops supplemented by 1000 mounted cavalrymen. Additional Persian resources included 200 or more supply ships and 50 or more horse carrying ships. The massive Persian force was to be defended against by only 10,000 Athenian hoplites and an additional 1000 Plataean soldiers. (Plataea being another Greek city.)

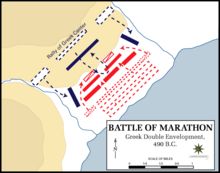

The outnumbered Greeks were sure to choose the battlefield wisely, and just as they would at Thermopylae forced the Persians to attack on a narrow front, with mountains and marshes channelizing the Persians and ruining any chance for the Persian cavalry to envelop the Greeks. Greek tactics were to use their “missile troops” (those that threw spears, javelins, arrows and other objects of weaponry) in the middle of an attack on the Persians, thus fooling the Persians into pouring their best troops into the center of the battle. The Greeks then turned both flanks of the Persians and descended upon the Persian center, causing panic and futile attempts at flight. The historian Herodotus reported only about 200 Greeks were killed compared to the loss of about 6400 Persians killed and the destruction of at least 7 Persian ships. Modern historians estimate Greek losses at between 1000 and 3000 dead and Persian losses at perhaps 5000 dead. Either way, the Persians were routed and Athens was for the time saved.

Although superior Persian forces still existed and plans were made to again attack the Athenians, Persian attention was diverted by unrest in Persian held Egypt that required immediate attention, allowing the Greeks a much needed respite. The Battle of Marathon proved Greeks had the ability to beat the mighty Persians and began a string of victories by the Greeks over the Persians. The Battle of Marathon also proved that Athens could be quite successful militarily without the aid of Sparta, a significant development in Greek political relationships.

Please Note: Historic sources of the Battle of Marathon are of dubious accuracy as they rely mainly on the historian, Herodotus, who was born 6 years after the battle was fought and presumably did not write about it until some years later. Many such famous historical events were written various amounts of time after the alleged events and details vary wildly from source to source. Historians must collate all the sources and decide on the most likely facts and figures involved, which of course is just an educated guess. Dates, numbers of troops, and the sequence of events may thus be somewhat different from the actual events. Please keep this in mind while reading about ancient battles and events.

Legends About the Battle of Marathon

The best known reminder of the Battle of Marathon is the footrace referred to as a “marathon.” A 26.2 mile footrace meant to commemorate the messenger Pheidippides that brought news of victory at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC back to Athens. Of all the marathons run each year, the Olympic race, closing the Summer Olympics as the last event every 4 years, is the most prestigious. Unlike those other marathons with hundreds or even thousands of contestants, only the best in the world compete for the Olympic Gold Medal and a place in history. In fact, the word “marathon” has come to mean any particularly long and arduous undertaking, such as the reminder that a major league baseball season is a “marathon, not a sprint.” Oddly enough, the legend of the “Marathon” run is probably conflated with the run made by Pheidippides to Sparta, a 140 mile run made according to legend in only about 36 hours.

Another lasting tribute to the Battle of Marathon is the word “panic,” which stems from the same Pheidippides, according to legend, having met the God Pan on his way to or from Sparta where he had been sent to seek aid for the coming battle from the Spartans. The Spartans refused to assist Athens, but the interaction between Pan and Pheidippides included Pan asking why Athens did not honor and pray to him. Pheidippides promised the God that henceforth Athens would well remember Pan in their prayers and praise, and Pan, believing the brave runner was truthful, assisted at the Battle of Marathon by instilling fear in the Persian soldiers, a fear we now call “panic” in honor of the God’s name.

The Athenians were not confining their prayers to only their patron Goddess, Athena, and the God Pan due to the experience of Pheidippides! No, they were carefully hedging their bets by also beseeching Artemis, Goddess of the Hunt, for her assistance in the coming battle. After the great victory, a festival was held in which the Athenians had promised to sacrifice a goat for every Persian soldier slain in the battle. The number of slain Persians exceeded the number of available goats, so the Athenians, practical as ever, slew 500 goats and promised the Goddess they would sacrifice 500 goats per year until the debt was paid. The Athenians were still sacrificing 500 goats per year 90 years later. (Note: The notion of “sacrifice” strikes us as kind of hollow when the festival goers end up eating the “sacrificed” animals, meaning there is not much actual sacrifice on the part of the Athenians!)

Question for students (and subscribers): Were you aware of the Battle of Marathon and it being the source of the familiar marathon races? Were you aware of the word “panic” and its origin at the Battle of Marathon? Did you know the modern American oil company named Marathon Oil was once one of the Standard Oil companies (originally the Ohio Oil Company, established 1887) that were split off when Standard Oil was broken up in 1911? (In 1930 they started the “Marathon” brand name and changed the name of the company to Marathon in 1962.) What other brands or places named “Marathon” can you think of? What do you think about the practice of “sacrificing” animals in an effort to gain God’s/a God’s favor? Please let us know in the comments section below this article.

If you liked this article and would like to receive notification of new articles, please feel welcome to subscribe to History and Headlines by liking us on Facebook and becoming one of our patrons!

Your readership is much appreciated!

Historical Evidence

For more information, please see…

Charles River Editors. The Most Famous Battles of the Ancient World: Marathon, Thermopylae, Salamis, Cannae, and the Teutoburg Forest. Charles River Editors, 2017.

Fink, Dennis. The Battle of Marathon in Scholarship: Research, Theories and Controversies Since 1850. McFarland, 2014.

The featured image in this article, a map of the initial disposition of forces at Marathon, is taken from http://www.dean.usma.edu/history/atlases/ancient_warfare/battle_marathon_initial.gif, in context http://www.dean.usma.edu/history/atlases/ancient_warfare/battle_marathon_initial.html. According to Wikimedia Commons, the following quotation is from an email querying copyright status of the map: “You are welcome to use the maps stated below for the purposes outlined in your document license. We do request the following credit line, “Maps Courtesy of the Department of History, United States Military Academy.”” Permission is therefore granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this image under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled GNU Free Documentation License.

You can also watch a video version of this article on YouTube: