A Brief History

On January 24, 1915, the British Royal Navy Grand Fleet fought a sizable naval engagement against elements of the German Imperial High Seas Fleet in the North Sea at an area called Dogger Bank. With all the attention the Battle of Jutland and the submarine war in the Atlantic get, it may be easy to forget there were other major naval engagements during World War I. Today we discuss one of those naval battles, a battle won by the British, although like Jutland, a not satisfying victory.

Digging Deeper

The battle area, Dogger Bank, is a 160 mile by 60 mile shallow area of the North Sea to the East of England where a landmass bridging Great Britain to mainland Europe once existed. The sandy bottom is only under 50 to 120 feet of water, and the area is known to fisherman as a productive fishing ground. Cod and herring are the predominant fish caught there, and the area is sometimes referred to as The Dogger Sea.

The Battle of Dogger Bank is notable for its origin, which is the interception and decoding of German radio transmissions between shore headquarters and its ships. Radio was fairly new to naval warfare and the business of signals intelligence was in its infancy. The stage for the radio intercepts was set by the British cutting of underwater telegraph cables forcing the Germans to communicate by radio between shore stations. In this case, such intelligence work paid off handsomely as the British were able to determine a powerful German task force was setting sail to conduct raiding on vital shipping to Britain as a sequel to a raid on British ports on the East coast of Great Britain conducted in December of 1914. The 1914 raid had also been detected by signals intelligence, but the information had been mishandled and the raid went off un-intercepted. A Royal Navy task force was sent to intercept the Germans on the January 1915 raid and foil the German plans for commerce raiding. A previous British naval victory at the Battle of Heligoland Bight in 1914 had left the German High Seas Fleet temporarily in the refuge of their home ports, leaving the Germans to plan such limited raids.

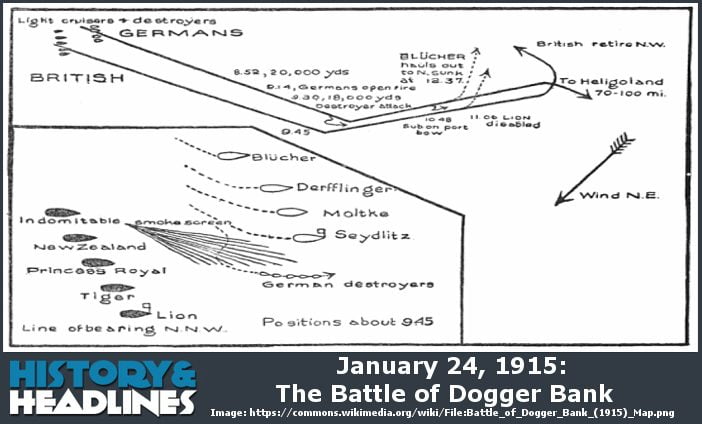

The German fleet consisted of 4 light cruisers, an armored cruiser, 3 battle cruisers, 18 destroyers and aerial support from a zeppelin. The British naval force sent to intercept the Germans consisted of 5 battle cruisers, 7 light cruisers and 35 destroyers which would seem to be a superior force. The German fleet was surprised when the British fleet showed up in force, spotting the telltale smoke of the British ships rapidly approaching the German fleet on the morning of January 24, 1915. Realizing surprise had been lost and that he was facing a larger force, the German commander, Admiral Franz Hipper, ordered his ships to flee to the Southeast at best speed. The Germans were hindered by their slowest ship, the armored cruiser Blücher, that could not possibly outrun the British force. Of course, not all the British ships shared equal speed, and some of the British ships had not caught up enough to engage in the opening of the battle.

While still sailing at high speed and at maximum gun range (11 miles), the British opened fire on the fleeing German ships. The British managed to get 5 of their larger ships close enough to engage 4 of the German vessels. The winds favored the British, by blowing the smoke from the coal fired boilers and from the discharge of the ships’ guns away from the optical sights of the gunners, while those same winds put smoke in the way of the German gunners attempting to fire back at the pursuing British ships. The German battlecruiser Seydlitz and the German armored cruiser Blücher were both hit and heavily damaged, while the British flagship, the battlecruiser HMS Lion was also hit by 12 inch shells, with 14 of the big shells striking the ship and putting her out of action. A single British destroyer was also damaged heavily enough to be placed out of action.

While the British fleet concentrated on the stricken and slowing Blücher the rest of the German fleet made haste to return to home port. Blücher continued to fight on her own, disabling the unlucky British destroyer and also landing hits on British battlecruisers with her secondary 8 inch armament. The German armored cruiser was fighting a losing battle and was sunk by torpedoes from a British light cruiser, taking 792 of her crew to the bottom. As the British attempted to rescue German survivors, the zeppelin made its appearance along with a seaplane, with both German aircraft dropping small bombs on the British ships without scoring any hits but disrupting rescue operations. The rest of the German ships successfully returned to port, largely because of the British flagship being damaged and her signal flags being misunderstood when Lion signaled she was heading to the Northeast and the other British ships took the signal as meaning they should head Northeast to engage the damaged Blücher. When British commander Admiral David Beatty realized the misunderstanding, he attempted to signal his ships to continue pursuit, but his signal flags could not be seen. Too late, the British fleet realized their blunder but by that time the Germans could no longer be caught. British lack of enthusiasm for pursuit was also affected by the fear of being torpedoed by German submarines that were not actually on the scene. In spite of the mix up caused by the signal flags, British Navy ships were still ordered to communicate with each other via signal flag and radio communication was to be conducted by the Admiralty from shore to ships.

The Germans had suffered the loss of Blücher and heavy damage to Seydlitz, with 954 killed, 189 captured and 80 men wounded. The battlecruiser Derfflinger also suffered damage from a single British shell, causing the British to believe the ship was much more seriously damaged than she actually was. The British suffered far less, with the battlecruiser Lion out of action along with a single destroyer and only 15 killed and 32 wounded. The British battlecruiser Tiger was also damaged, and this time it was the Germans that erroneously thought that ship had been sunk.. Despite the apparent victory, British naval bosses were incensed at the lost opportunity to have inflicted much greater punishment on the German fleet and Beatty was duly blamed for his failure. Additionally, the Germans had scored 22 hits with major caliber gunfire to a paltry 7 hits by the British big guns, and in spite of the sinking of Blücher the British ships proved more susceptible to battle damage than the German ships. Admiral Hipper was fired and replaced by the German Navy, and the Germans were left believing that their foray had been revealed to the British by a spy, not realizing the part signals intelligence had played in the battle.

The interception of radio traffic between shore and ships was to become a major factor during World War II, with both the Germans and British using the techniques to great effect during the Battle of the Atlantic. In the Pacific, the United States used signals intelligence to enormous effect in defeating the Japanese Imperial Navy, especially at the Battle of Midway.

Question for students (and subscribers): Did you know radio intelligence played a part in World War I? Have you previously heard of the Battle of Dogger Bank? Do you believe Admiral Hipper deserved to be fired? Please let us know in the comments section below this article.

If you liked this article and would like to receive notification of new articles, please feel welcome to subscribe to History and Headlines by liking us on Facebook and becoming one of our patrons!

Your readership is much appreciated!

Historical Evidence

For more information, please see…

Cosentino, Michele and Ruggero Stanglini. British and German Battlecruisers: Their Development and Operations. Naval Institute Press, 2016.

Sondhaus, Lawrence. The Great War at Sea: A Naval History of the First World War. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Staff, Gary. German Battlecruisers of World War One: Their Design, Construction and Operations. Naval Institute Press, 2014.

The featured image in this article, a map showing British and German ships and movements at the Battle of Dogger Bank, 24 January 1915, from William Oliver Stevens and Allan Westcott, A History of Sea Power (New York: George H Doran Company, 1920), downloaded from Project Gutenberg at http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/24797, is in the public domain in the United States. This applies to U.S. works where the copyright has expired, often because its first publication occurred prior to January 1, 1924. See this page for further explanation.